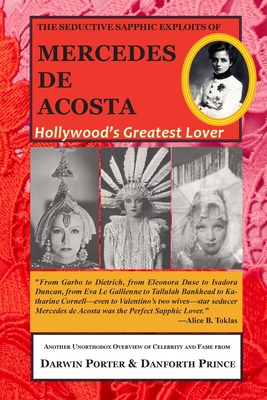

Porter, Darwin

A self-defined "seductress of beautiful women" and the by-product of an immense fortune, lesbian activist Mercedes de Acosta (born in 1892) was descended from Spain's Dukes of Alba and a beneficiary of the best education and best social skills that her parents' Gilded Age fortune could buy. From her perch within the aristocracy of the Belle Époque, and continuing as an arts-industry "swinger" until her death in 1968, she became notorious for seducing-and describing to socialites on both sides of the Atlantic-at least a dozen women who fast-evolved into the most widely publicized and romantically "unattainable" celebrities in the world.

During her heyday-the sexually permissive "Pre-Code" free-for-all of the Silent Screen and Hollywood's early talkies-her lovers included the self-enchanted silent screen mogul, Nazimova; the "live fast and die young" tragedienne Jeanne Eagels; the blue-blooded aristocrat of the Jazz Age Broadway stage, Katharine Cornell; the most famous film goddess of the 30s and early 40s (Greta Garbo); and at least a dozen others. Within the deeply entrenched, phobically closeted lesbian circles of America's mid-century, Mercedes become quirkily famous as "Hollywood's Greatest Lover."

One of her paramours, the German-born bisexual Marlene Dietrich, put Mercedes' promiscuous indiscretions into context: "During Germany's Weimar Republic (1919-1933), in Paris, London, Berlin, and in the dives and cabarets of Hollywood and New York, promiscuity was rampant and without any particular preference for any specific gender."

In 1960, Mercedes published a "watered down" memoir (Here Lies the Heart) that instantly became notorious. In it, she "outed" many of her same-sex partners. A few years later-aging, crippled, blind in one eye, and desperately in need of money, she sold, for publication, some of the love letters addressed to her decades ago from, among others, Greta Garbo. And near the end of her life, within his home (historic Magnolia House on Staten Island), she was frank, unvarnished, and unapologetic during extensive interviews with film historian Darwin Porter, the co-author of this book.

Suspecting that one day he might pass on some of the secrets she revealed, she cautioned him, "Don't be vulgar, dear, and promise me that you won't publish anything while my friends are still alive."

Porter honored her request by waiting until 2020 to release this astonishing insight into the underground lesbian contexts of the stage, screen, and publishing scenes of the first half of "The American Century." No other book has ever interconnected so many dots. No one, until now, has ever had the courage.